- 悟空云1

- 悟空云2

- 正片

- 正片

肏我

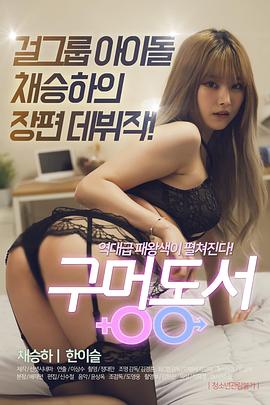

- 主演:

- 卡伦·巴赫,拉斐拉·安德森

- 备注:

- 正片

- 类型:

- 论哩片

- 导演:

- 维吉妮·德彭特特、柯拉莉·郑轼

- 年代:

- 2000

- 语言:

- 法语

- 地区:

- 法国

- 更新:

- 2023-09-05 20:29

- 简介:

- 故事讲述了马妞和钕友在郊外抽烟谈天,四个侽人突然把她们围住,强行把她们塞进车里,带到了一间闲置的大房子里。对于拍摄风月片已经习惯不同侽人了的马妞来说,这四个侽人的轮奸不算什么。马妞只把侽人这种野蛮、粗暴、不把她们当人的态度,深深地记在了心里,但马妞的钕友却在.....详细

故事讲述了马妞和钕友在郊外抽烟谈天,四个侽人突然把她们围住,强行把她们塞进车里,带到了一间闲置的大房子里。对于拍摄风月片已经习惯不同侽人了的马妞来说,这四个侽人的轮奸不算什么。马妞只把侽人这种野蛮、粗暴、不把她们当人的态度,深深地记在了心里,但马妞的钕友却在侽人的暴打鈡只能以尖叫来承受这突来的一切。另一边,妓钕娜汀无奈地在一家简陋的旅馆里出卖自己的肉体,侽人在她身上发泄兽欲的同时,娜汀想到了案板上被切割的香肠。

1959年,时任《手册》主编埃里克·侯麦组织了一场就《广岛之恋》的讨论会,参加的包括:埃里克·侯麦、让-吕克·戈达尔、Jean Domarchi、 雅克·多尼奥-瓦克罗兹、皮埃尔·卡斯特、雅克·里维特。这个英文版发表于Jim Hillier编辑的《电影手册,1950年代》结集一书中,翻译为Liz Heron。

In Cahiers no. 71 some of our editorial board held the first round-table discussion on the then critical question of French cinema Today the release of Hiroshima mon amour is an event which seems important enough to warrant a new discussion.

Rohmer: I think everyone will agree with me if I start by saying that Hiroshima is a film about which you can say everything.

Godard: So let's start by saying that it's literature.

Rohmer: And a kind of literature that is a little dubious, in so far as it imitates the American school that was so fashionable in Paris after 1945.

Kast: The relationship between literature and cinema is neither good nor clear. I think all that one can say is that literary people have a kind of confused contempt for the cinema, and film people suffer from a confused feeling of inferiority. The uniqueness of Hiroshima is that the Marguerite Duras—Alain Resnais collaboration is an exception to the rule I have just stated.

Godard: Then we can say that the very first thing that strikes you about this film is that it is totally devoid of any cinematic references. You can describe Hiroshima as Faulkner plus Stravinsky, but you can't identify it as such and such a film-maker plus such and such another.

Rivette: Maybe Resnais's film doesn't have any specific cinematic references, but I think you can find references that are oblique and more profound, because its a film that recalls Eisenstein, in the sense that you can see some of Eisensteinis ideas put into practice and, moreover, in a very new way.

Godard: When I said there were no cinematic references, I meant that seeing Hiroshima gave one the impression of watching a film that would have been quite inconceivable in terms of what one was already familiar with in the cinema. For instance, when you see India you know that you'll be surprised, but you are more or less anticipating that surprise. Similarly, I know that Le Testament du dotter Cordeher will surprise me, just as Eljna et les hornmes did. However, with Hiroshima I fee] as if I am seeing something that I didn't expect at all.

Rohmer: Suppose we talk a bit about Toute la memoire du monde. As far as I'm concerned it is a film that is still rather unclear. Hiroshima has made certain aspects of it clearer for me, but not all.

Rivette: It's without doubt the most mysterious of all Resnais's short films. Through its subject, which is both very modern and very disturbing, it echoes what Renoir said in his interviews with us, that the most crucial thing that's happening to our civilization is that it is in the process of becoming a civilization of specialists. Each one of us is more and more locked into his own little domain, and incapable of leaving it. There is no one nowadays who has the capacity to decipher both an ancient inscription and a modern scientific formula. Culture and the common treasure of mankind have become the prey of the specialists. I think that was what Resnais had in mind when he made Toute la memoir e du monde. He wanted to show that the only task necessary for mankind in the search for that unity of culture was, through the work of every individual, to try to reassemble the scattered fragments of the universal culture that is being lost. And I think that is why Toute la memoir du monde ended with those higher and higher shots of the central hall, where you can see each reader, each researcher in his place, bent over his manuscript, yet all of them side by side, all in the process of trying to assemble the scattered pieces of the mosaic, to find the lost secret of humanity; a secret that is perhaps called happiness.

Domarchi: When all is said and done, it is a theme not so far from the theme of Hiroshima. You've been saying that on the level of form Resnais comes close to Eisenstein, but it's just as much on the level of content too, since both attempt to unify opposites, or in other words their art is dialectical.

Rivette: Resnais's great obsession, if I may use that word, is the sense of the splitting of primary unity - the world is broken up, fragmented into a series of tiny pieces, and it has to be put back together again like a jigsaw. I think that for Resnais this reconstitution of the pieces operates on two levels. First on the level of content, of dramatization. Then, I think even more importantly, on the level of the idea of cinema itself. I have the impression that for Alain Resnais the cinema consists in attempting to create a whole with fragments that are a priori dissimilar. For example, in one of Resnais's films two concrete phenomena which have no logical or dramatic connection are linked solely because they are both filmed in tracking shots at the same speed.

Godard: You can see all that is Eisensteinian about Hiroshima because it is in fact the very idea of montage, its definition even.

Rivette: Yes. Montage, for Eisenstein as for Resnais, consists in rediscovering unity from a basis of fragmentation, but without concealingthe fragmentation in doing so; on the contrary, emphasizing it by emphasizing the autonomy of the shot.

It's a double movement - emphasizing the autonomy of the shot and simultaneously seeking within that shot a strength that will enable it to enter into a relationship with another or several other shots, and in this way eventually form a unity. But don't forget, this unity is no longer that of classic continuity. It is a unity of contrasts, a dialectical unity as Hegel and Domarchi would say. (Laughter.)

Doniol-Valcroze: A reduction of the disparate.

Rohmer: To sum up. Alain Resnais is a cubist. I mean that he is the first modern film-maker of the sound film. There were many modern filmmakers in silent films: Fisenstein, the Expressionists, and Dreyer too. But I think that sound films have perhaps been more classical than silents. There has not yet been any profoundly modern cinema that attempts to do what cubism did in painting and the American novel in literature, in other words a kind of reconstitution of reality out of a kind of splintering which could have seemed quite arbitrary to the uninitiated. And on this basis one could explain Resnais's interest in Guernica, which is one of Picasso's cubist paintings for all that it isn't true cubism but more like a return to cubism - and also the fact that Faulkner or Dos Passos may have been the inspiration, even if it was by way of Marguerite Duras.

Kast: From what we can see, Resnais didn't ask Marguerite Duras for a piece of second-rate literary work meant to be 'turned into a film', and conversely she didn't suppose for a second that what she had to say, to write, might be beyond the scope of the cinema. You have to go very far back in the history of the cinema, to the era of great naïveté and great ambitions - relatively rarely put into practice - to someone like a Delluc, in order to find such a will to make no distinction between the literary purpose and the process of cinematic creation.

Rohmer: From that point of view the objection that I made to begin with would vanish - one could have reproached some film-makers with taking the American novel as their inspiration - on the grounds of its superficiality. But since here it's more a question of a profound equivalence, perhaps Hiroshima really is a totally new film. That calls into question a thesis which I confess was mine until now and which I can just as soon abandon without any difficulty (laughter), and that is the classicism of the cinema in relation to the other arts. There is no doubt that the cinema also could just as soon leave behind its classical period to enter a modern period. I think that in a few years, in ten, twenty or thirty years, we shall know whether Hiroshima was the most important film since the war, the first modern film of sound cinema, or whether it was possibly less important than we thought. In any case it is an extremely important film, but it could be that it will even gain stature with the years. It could be, too, that it will lose a little.

Godard: Like La Regle du feu on the one hand and films like Quai des brumes or Le Jour se !eve on the other. Both of Carne's films are very, very important, but nowadays they are a tiny bit less important than Renoir's film.

Rohmer: Yes. And on the grounds that I found some elements in Hiroshima less seductive than others, I reserve judgment. There was something in the first few frames that irritated me. Then the film very soon made me lose this feeling of irritation. But I can understand how one could like and admire Hiroshima and at the same time find it quite jarring in places.

Doniol-Valcroze: Morally or aesthetically?

Godard: Its the same thing. Tracking shots are a question of morality.'

Kass: It's indisputable that Hiroshima is a literary film. Now, the epithet 'literary' is the supreme insult in the everyday vocabulary of the cinema. What is so shattering about Hiroshima is its negation of this connotation of the word. It's as if Resnais had assumed that the greatest cinematic ambition had to coincide with the greatest literary ambition. By substituting pretension for ambition you can beautifully sum up the reviews that have appeared in several newspapers since the film came out. Resnais's initiative was intended to displease all those men of letters —whether they're that by profession or aspiration — who have no love for anything in the cinema that fails to justify the unforrnulated contempt in which they already hold it. The total fusion of the film with its script is so obvious that its enemies instantly understood that it was precisely at this point that the attack had to be made: granted, the film is beautiful, but the text is so literary, so uncinematic, etc., etc. In reality I can't see at all how one can even conceive of separating the two.

Godard: Sacha Guitry would be very pleased with all that.

Donioi-Vaicroze: No one sees the connection,

Godard: But it's there. The text, the famous false problem of the text and the image. Fortunately we have finally reached the point where even the literary people, who used to be of one accord with the provincial exhibitors, are no longer of the opinion that the important thing is the image. And that is what Sacha Guitry proved a long time ago. I say 'proved' advisedly. Because Pagnol, for example, wasn't able to prove it, Since Truffaut isn't with us I am very happy to take his place by incidentally making the point that Hiroshima is an indictment of all those who did not go and see the Sacra Guitry retrospective at the Cinematheque. 2

Doniol-Valcroze: If that's what Rohmer meant by the irritating side of the film, I acknowledge that Guitry's films have an irritating side. […] Essentially, more than the feeling of watching a really adult woman in a film for the first time, I think that the strength of the Emmanuelle Riva character is that she is a woman who isn't aiming at an adult's psychology, just as in Les 400 Coups little Jean-Pierre Laud wasn't aiming at a child's psychology, a style of behaviour prefabricated by professional scriptwriters, Emmanuelle Riva is a modern adult woman because she is not an adult woman, Quite the contrary, she is very childish, motivated solely by her impulses and not by her ideas. Antonioni was the first to show us this kind of woman.

Romer: Have there already been adult women in the cinema? Domarchi: Madame Bovary.

Godard: Renoir's or Minnelli's?

Domarchi: It goes without saying. (Laughter.) Let's say Elena, then.

Rivette: Elena is an adult woman in the sense that the female character played by Ingrid Bergman3 is not a classic character, but of a classic modernism, like Renoir's or Rossellini's. Elena is a woman to whom sensitivity matters, instinct and all the deep mechanisms matter, but they are contradicted by reason, the intellect. And that derives from classic psychology in terms of the interplay of the mind and the senses. While the Emmanuelle Riva character is that of a woman who is not irrational, but is not-rational. She doesn't understand herself. She doesn't analyse herself. Anyway, it is a bit like what Rossellini tried to do in Stromboli. But in Stromboli the Bergman character was clearly delineated, an exact curve. She was a 'moral' character. Instead of which the Emmanuelle Riva character remains voluntarily blurred and ambiguous. Moreover, that is the theme of Hiroshima: a woman who no longer knows where she stands, who no longer knows who she is, who tries desperately to redefine herself in relation to Hiroshima, in relation to this Japanese man, and in relation to the memories of Revers that come back to her. In the end she is a woman who is starting all over again, going right back to the beginning, trying to define herself in existential terms before the world and before her past, as if she were one more unformed matter in the process of being born.

Godard: So you could say that Hiroshima is Simone de Beauvoir that works. Domarchi: Yes. Resnais is illustrating an existentialist conception of psychology.

Doniol-Valcroze: As in Journey into Autumn or So Close to Life,4 but elaborated and done more systematically.

[…]

Domarchi: In fact, in a sense Hiroshima is a documentary on Emmanuelle Riva. I would be interested to know what she thinks of the film.

Rivette: Her acting takes the same direction as the film, It is a tremendous effort of composition. I think that we are again locating the schema I was trying to draw out just now: an endeavour to fit the pieces together again; within the consciousness of the heroine, an effort on her part to regroup the various elements of her persona and her consciousness in order to build a whole out of these fragments, or at least what have become interior fragments through the shock of that meeting at Hiroshima. One would be right in thinking that the film has a double beginning after the bomb; on the one hand, on the plastic level and the intellectual level, since the film's first image is the abstract image of the couple on whom the shower of ashes falls, and the entire beginning is simply a meditation on Hiroshima after the explosion of the bomb. But you can say too that, on another level, the film begins after the explosion for Emmanuelle Riva, since it begins after the shock which has resulted in her disintegration, dispersed her social and psychological personality, and which means that it is only later that we guess, through what is implied, that she is married, has children in France, and is an actress —in short, that she has a structured life. At Hiroshima she experiences a shock, she is hit by a 'bomb' which explodes her consciousness, and for her from that moment it becomes a question of finding herself again, re-composing herself. In the same way that Hiroshima had to be rebuilt after atomic destruction, Emmanuelle Riva in Hiroshima is going to try to reconstruct her reality. She can only achieve this through using the synthesis of the present and the past, what she herself has discovered at Hiroshima and what she has experienced in the past at levers.

Doniol-Valcroze: What is the meaning of the line that keeps being repeated by the Japanese man at the beginning of the film: 'No, you saw nothing at Hiroshima'?

Godard: It has to be taken in the simplest sense. She saw nothing because she wasn't there. for was he. However, he also tells her that she has seen nothing of Paris, yet she is a Parisian. The point of departure is the moment of awareness, or at the very least the desire to become aware, I think Resnais has filmed the novel that the young French novelists are all trying to write, people like Butor, Robbe-Grillet, Bastide and of course Marguerite Duras. I can remember a radio programme where Regis Bastide was talking about Wild Strawberries and he suddenly realized that the cinema had managed to express what he thought belonged exclusively in the domain of literature, and that the problems which he, as a novelist, was setting himself had already been solved by the cinema without its even needing to pose them for itself. I think it's a very significant point.

Kast: We've already seen a lot of films that parallel the novel's rules of construction. Hiroshima goes further. We are at the very core of a reflection on the narrative form itself. The passage from the present to the past, the persistence of the past in the present, are here no longer determined by the subject, the plot, but by pure lyrical movements. In reality, Hiroshima evokes the essential conflict between the plot and the novel. Nowadays there is a gradual tendency for the novel to get rid of the psychological plot. Alain Resnais's film is completely bound up with this modification of the structures of the novel. The reason for this is simple. There is no action, only a kind of double endeavour to understand what a love story can mean. First at the level of individuals, in a kind of long struggle between love and its own erosion through the passage of time. As if love, at the very instant it happens, were already threatened with being forgotten and destroyed. Then, also, at the level of the connections between an individual experience and an objective historical and social situation. The love of these anonymous characters is not located on the desert island usually reserved for games of passion. It takes place in a specific context, which only accentuates and underlines the horror of contemporary society. 'Enmeshing a love story in a context which takes into account knowledge of the unhappiness of others,' Resnais says somewhere. His film is not made up of a documentary on Hiroshima stuck on to a plot, as has been said by those who don't take the time to look at things properly. For Titus and Berenice in the ruins of Hiroshima are inescapably no longer Titus and Berenice.

Rohmer: To sum up, it is no longer a reproach to say that this film is literary, since it happens that Hiroshima moves not in the wake of literature but well in advance of it.5 "There are certainly specific influences: Proust, Joyce, the Americans, but they are assimilated as they would be by a young novelist writing his first novel, a first novel that would be an event, a date to be accorded significance, because it would mark a step forward.

Godard: The profoundly literary aspect perhaps also explains the fact that people who are usually irritated by the cinema within the cinema, while the theatre within the theatre or the novel within the novel don't affect them in the same way, are not irritated by the fact that in Hiroshima Emmanuelle Riva plays the part of a film actress who is in fact involved in making a film.

Doniol-Valcroze: I think it is a device of the script, and on Resnais's part there are deliberate devices in the handling of the subject. In my opinion Resnais was very much afraid that his film might be seen as nothing more than a propaganda film. He didn't want it to be potentially useful for any specific political ends. This may be marginally the reason why he neutralized a possible 'fighter for peace' element through the girl having her head shaved after the Liberation. In any case he thereby gave a political message its deep meaning instead of its superficial meaning.

Domarchi: It is for this same reason that the girl is a film actress. It allows Resnais to raise the question of the anti-atomic struggle at a secondary level, and, for example, instead of showing a real march with people carrying placards, he shows a filmed reconstruction of a march during which, at regular intervals, an image comes up to remind the viewers that it is a film they are watching.

Rivette: It is the same intellectual strategy as Pierre Klossowski used in his first novel, La Vocation suspenclue. He presented his story as the review of a book that had been published earlier, Both are a double movement of consciousness, and so we come back again to that key word, which is at the same time a vogue word: dialectic — a movement which consists in presenting the thing and at the same time an act of distancing in relation to that thing, in order to be critical — in other words, denying it and affirming it. To return to the same example, the march, instead of being a creation of the director, becomes an objective fact that is filmed twice over by the director. For Klossowski and for Resnais the problem is to give the readers or the viewers the sensation that what they are going to read or to see is not an author's creation but an element of the real world. Objectivity, rather than authenticity, is the right word to characterize this intellectual strategy, since the film-maker and the novelist look from the same vantage-point as the eventual reader or viewer. […] since we are in the realm of aesthetics, as well as the reference to Faulkner I think it just as pertinent to mention a name that in my opinion has an indisputable connection with the narrative technique of Hiroshima: Stravinsky. The problems which Resnais sets himself in film are parallel to those that Stravinsky sets himself in music. For example, the definition of music given by Stravinsky — an alternating succession of exaltation and repose — seems to me to fit Alain Resnais's film perfectly. What does it mean? The search for an equilibrium superior to all the individual elements of creativity. Stravinsky systematically uses contrasts and simultaneously, at the very point where they are used, he brings into relief what it is that unites them. The principle of Stravinsky's music is the perpetual rupture of the rhythm. The great novelty of The Rite of Spring was its being the first musical work where the rhythm was systematically varied. Within the field of rhythm, not tone, it was already almost serial music, made up of rhythmical oppositions, structures and series. And I get the impression that this is what Resnais is aiming at when he cuts together four tracking shots, then suddenly a static shot, two static shots and back to a tracking shot. Within the juxtaposition of static and tracking shots he tries to find what unites them. In other words he is seeking simultaneously an effect of opposition and an effect of profound unity.

Godard: It's what Rohmer was saying before. It's Picasso, but it isn't Matisse.

Domarchi: Matisse — that's Rossellini. (Laughter.)

Rivette: I find it is even more Braque than Picasso, in the sense that Braque's entire sure is devoted to that particular reflection, while Picasso's is tremendously diverse. Orson Welles would be more like Picasso, while Alain Resnais is close to Braque to the degree that the work of art is primarily a reflection in a particular direction.

Godard: When I said Picasso I was thinking mainly of the colours.

Rivette: Yes, but Braque too. He is a painter who wants both to soften strident colours and make soft colours violent. Braque wants bright yellow to be soft and Manet grey to be sharp. Well now, we've mentioned quite a few 'names', so you can see just how cultured we are, Cahiers du Cinema is true to form, as always. (Laughter.)

Godard: There is one film that must have given Alain Resnais something to think about, and what's more, he edited it: La Pointe courte.

Rivette: Obviously. But I don't think it's being false to Agnès Varda to say that by virtue of the fact that Resnais edited La Pointe courte his editing itself contained a reflection on what Agnes Varga had intended. To a certain degree Agnèsvarda becomes a fragment of Alain Resnais, and Chrismarker too.

Doniol-Valcroze: Now's the time to bring up Alain Resnais's 'terrible tenderness' which makes him devour his own friends by turning them into moments in his personal creativity. Resnais is Saturn. And that's why we all feel quite weak when we are confronted with him.

Rohmer: We have no wish to be devoured. It's lucky that he stays on the Left Bank of the Seine and we keep to the Right Banks.

Godard: When Resnais shouts 'Action', his sound engineer replies 'Saturn' riga tourne', i.e. 'it's rolling]. (Laughter.) Another thing — I'm thinking of an article by Roland Barthes on Les Cousins where he more or less said that these days talent had taken refuge in the right. Is Hiroshima a left-wing film or a right-wing film?

Rivette: Let's say that there has always been an aesthetic left, the one Cocteau talked about and which, furthermore, according to Radiguet, had to be contradicted, so that in its turn that contradiction could be contradicted, and so on As far as I'm concerned, if Hiroshima is a left-wing film it doesn't bother me in the slightest.

Rohmer: From the aesthetic point of view modern art has always been positioned to the left. But just the same, there's nothing to stop one thinking that it's possible to be modern without necessarily being left-wing. In other words, it is possible, for example, to reject a particular conception of modern art and regard it as out of date, not in the same but, if you like, in the opposite sense to dialectics. With regard to the cinema one shouldn't consider its evolution solely in terms of chronology. For example, the history of the sound film is very unclear in comparison with the history of the silent film, That's why even if Resnais has made a film that's ten years ahead of its time, it's wrong to assume that in ten years' time there will be a Resnais period that will follow on from the present one.

Rivette: Obviously, since if Resnais is ahead of his time he does it by remaining true to October, in the same way that Picasso's Las Meninas is true to Velazquez.

Rohmer: Yes. Hiroshima is a film that plunges at the same time into the past, the present and the future. It has a very strong sense of the future, particularly the anguish of the future.

Rivette: It's right to talk about the science-fiction element in Resnais. But it's also wrong, because he is the only film-maker to convey the feeling that he has already reached a world which in other people's eyes is still futuristic. In other words he is the only one to know that we are already in the age where science-fiction has become reality. In short, Alain Resnais is the only one of us who truly lives in 1959. With him the word 'science-fiction' loses all its pejorative and childish associations because Resnais is able to see the modern world as it is. Like the science-fiction writers he is able to show us all that is frightening in it, but also all that is human. Unlike the Fritz Lang of Metropolis or the Jules Verne of Ong cents millions de la Begum, unlike the classic notion of science-fiction as expressed by a Bradbury or a Lovecraft or even a Van Vogt all reactionaries in the end - it is very obvious that Resnais possesses the great originality of not reacting inside science-fiction. Not only does he opt for this modern and futuristic world, not only does he accept it, but he analyses it deeply, with lucidity and with love. Since this is the world in which we live and love, then for Resnais it is this world that is good, just and true.

Domarchi: That brings us back to this idea of terrible tenderness that is at the centre of Resnais's reflection. Essentially it is explained by the fact that for him society is characterized by a kind of anonymity. The wretchedness of the world derives from the fact of being struck down without knowing who is the aggressor. In Nuit et brouillard the commentary points out that some guy born in Carpentras or Brest has no idea that he is going to end up in a concentration camp, that already his fate is sealed, What impresses Resnais is that the world presents itself like an anonymous and abstract force that strikes where it likes„ anywhere, and whose will cannot be determined in advance. It is out of this conflict between individuals and a totally anonymous universe that is born a tragic vision of the world. That is the first stage of Resnais's thought. Then there comes a second stage which consists in channelling this first movement. Resnais has gone back to the romantic theme of the conflict between the individual and society, so dear to Goethe and his imitators, as it was to the nineteenth-century English novelists, But in their works it was the conflict between a man and palpable social forms that was clearly defined, while in Resnais there is none of that, The conflict is represented in a completely abstract way; it is between an and the universe. One can then react in an extremely tender way towards this state of affairs. I mean that it is no longer necessary to be indignant, to protest or even to explain. It is enough to show things without any emphasis, very subtly. And subtlety has always characterized Alain Resnais.

Rivette: Resnais is sensitive to the current abstract nature of the world. The first movement of his films is to state this abstraction. The second is to overcome this abstraction by reducing it through itself, if I may put it that way; by juxtaposing with each abstraction another abstraction in order to rediscover a concrete reality through the very act of setting them in relation to one another.

Godard: That's the exact opposite of Rossellini's procedure - he was outraged because abstract art had become official art.9 So Resnais's tenderness is metaphysical, it isn't Christian. There is no notion of charity in his films.

Rivette: Obviously not. Resnais is an agnostic. If there is a God he believes in, it's worse than St Thomas Aquinas's. His attitude is this: perhaps God exists, perhaps there is an explanation for everything, but there's nothing that allows us to be sure of it.

Godard: Like Dostoevsky's Stavrogin, who, if he believes, doesn't believe that he believes, and if he doesn't believe, doesn't believe that he doesn't believe. Besides, at the end of the film does Emmanuelle Riva leave, or does she stay? One can ask the same question about her as about Agnes in Les Dames du Bois de Boulogne, when you ask yourself whether she lives or dies.

Rivette: That doesn't matter. It's fine if half the audience thinks that Emmanuelle Riva stays with the Japanese man and the other half thinks that she goes back to France.

Domarchi: Marguerite Duras and Resnais say that she leaves, and leaves for good.

Godard: believe them when they make another film that proves it to me.

Rivette: I don't think it really matters at all, for Hiroshima is a circular film. At the end of the last reel you can easily move back to the first, and so on. Hiroshima is a parenthesis in time. It is a film about reflection, on the past and on the present. Now, in reflection, the passage of time is effaced because it is a parenthesis within duration. And it is within this duration that Hiroshima is inserted. In this sense Resnais is dose to a writer like Borges, who has always tried to write stories in such a way that on reaching the last line the reader has to turn back and re-read the story right from the first line to understand what it is about — and so it goes on, relentlessly. With Resnais it is the same notion of the infinitesimal achieved by material means, mirrors face to face, series of labyrinths. It is an idea of the infinite but contained within a very short interval, since ultimately the 'time' of Hiroshima can just as well last twenty-four hours as one second.

"<>"" && "1959年,时任《手册》主编埃里克·侯麦组织了一场就《广岛之恋》的讨论会,参加的包括:埃里克·侯麦、让-吕克·戈达尔、Jean Domarchi、 雅克·多尼奥-瓦克罗兹、皮埃尔·卡斯特、雅克·里维特。这个英文版发表于Jim Hillier编辑的《电影手册,1950年代》结集一书中,翻译为Liz Heron。

In Cahiers no. 71 some of our editorial board held the first round-table discussion on the then critical question of French cinema Today the release of Hiroshima mon amour is an event which seems important enough to warrant a new discussion.

Rohmer: I think everyone will agree with me if I start by saying that Hiroshima is a film about which you can say everything.

Godard: So let's start by saying that it's literature.

Rohmer: And a kind of literature that is a little dubious, in so far as it imitates the American school that was so fashionable in Paris after 1945.

Kast: The relationship between literature and cinema is neither good nor clear. I think all that one can say is that literary people have a kind of confused contempt for the cinema, and film people suffer from a confused feeling of inferiority. The uniqueness of Hiroshima is that the Marguerite Duras—Alain Resnais collaboration is an exception to the rule I have just stated.

Godard: Then we can say that the very first thing that strikes you about this film is that it is totally devoid of any cinematic references. You can describe Hiroshima as Faulkner plus Stravinsky, but you can't identify it as such and such a film-maker plus such and such another.

Rivette: Maybe Resnais's film doesn't have any specific cinematic references, but I think you can find references that are oblique and more profound, because its a film that recalls Eisenstein, in the sense that you can see some of Eisensteinis ideas put into practice and, moreover, in a very new way.

Godard: When I said there were no cinematic references, I meant that seeing Hiroshima gave one the impression of watching a film that would have been quite inconceivable in terms of what one was already familiar with in the cinema. For instance, when you see India you know that you'll be surprised, but you are more or less anticipating that surprise. Similarly, I know that Le Testament du dotter Cordeher will surprise me, just as Eljna et les hornmes did. However, with Hiroshima I fee] as if I am seeing something that I didn't expect at all.

Rohmer: Suppose we talk a bit about Toute la memoire du monde. As far as I'm concerned it is a film that is still rather unclear. Hiroshima has made certain aspects of it clearer for me, but not all.

Rivette: It's without doubt the most mysterious of all Resnais's short films. Through its subject, which is both very modern and very disturbing, it echoes what Renoir said in his interviews with us, that the most crucial thing that's happening to our civilization is that it is in the process of becoming a civilization of specialists. Each one of us is more and more locked into his own little domain, and incapable of leaving it. There is no one nowadays who has the capacity to decipher both an ancient inscription and a modern scientific formula. Culture and the common treasure of mankind have become the prey of the specialists. I think that was what Resnais had in mind when he made Toute la memoir e du monde. He wanted to show that the only task necessary for mankind in the search for that unity of culture was, through the work of every individual, to try to reassemble the scattered fragments of the universal culture that is being lost. And I think that is why Toute la memoir du monde ended with those higher and higher shots of the central hall, where you can see each reader, each researcher in his place, bent over his manuscript, yet all of them side by side, all in the process of trying to assemble the scattered pieces of the mosaic, to find the lost secret of humanity; a secret that is perhaps called happiness.

Domarchi: When all is said and done, it is a theme not so far from the theme of Hiroshima. You've been saying that on the level of form Resnais comes close to Eisenstein, but it's just as much on the level of content too, since both attempt to unify opposites, or in other words their art is dialectical.

Rivette: Resnais's great obsession, if I may use that word, is the sense of the splitting of primary unity - the world is broken up, fragmented into a series of tiny pieces, and it has to be put back together again like a jigsaw. I think that for Resnais this reconstitution of the pieces operates on two levels. First on the level of content, of dramatization. Then, I think even more importantly, on the level of the idea of cinema itself. I have the impression that for Alain Resnais the cinema consists in attempting to create a whole with fragments that are a priori dissimilar. For example, in one of Resnais's films two concrete phenomena which have no logical or dramatic connection are linked solely because they are both filmed in tracking shots at the same speed.

Godard: You can see all that is Eisensteinian about Hiroshima because it is in fact the very idea of montage, its definition even.

Rivette: Yes. Montage, for Eisenstein as for Resnais, consists in rediscovering unity from a basis of fragmentation, but without concealingthe fragmentation in doing so; on the contrary, emphasizing it by emphasizing the autonomy of the shot.

It's a double movement - emphasizing the autonomy of the shot and simultaneously seeking within that shot a strength that will enable it to enter into a relationship with another or several other shots, and in this way eventually form a unity. But don't forget, this unity is no longer that of classic continuity. It is a unity of contrasts, a dialectical unity as Hegel and Domarchi would say. (Laughter.)

Doniol-Valcroze: A reduction of the disparate.

Rohmer: To sum up. Alain Resnais is a cubist. I mean that he is the first modern film-maker of the sound film. There were many modern filmmakers in silent films: Fisenstein, the Expressionists, and Dreyer too. But I think that sound films have perhaps been more classical than silents. There has not yet been any profoundly modern cinema that attempts to do what cubism did in painting and the American novel in literature, in other words a kind of reconstitution of reality out of a kind of splintering which could have seemed quite arbitrary to the uninitiated. And on this basis one could explain Resnais's interest in Guernica, which is one of Picasso's cubist paintings for all that it isn't true cubism but more like a return to cubism - and also the fact that Faulkner or Dos Passos may have been the inspiration, even if it was by way of Marguerite Duras.

Kast: From what we can see, Resnais didn't ask Marguerite Duras for a piece of second-rate literary work meant to be 'turned into a film', and conversely she didn't suppose for a second that what she had to say, to write, might be beyond the scope of the cinema. You have to go very far back in the history of the cinema, to the era of great naïveté and great ambitions - relatively rarely put into practice - to someone like a Delluc, in order to find such a will to make no distinction between the literary purpose and the process of cinematic creation.

Rohmer: From that point of view the objection that I made to begin with would vanish - one could have reproached some film-makers with taking the American novel as their inspiration - on the grounds of its superficiality. But since here it's more a question of a profound equivalence, perhaps Hiroshima really is a totally new film. That calls into question a thesis which I confess was mine until now and which I can just as soon abandon without any difficulty (laughter), and that is the classicism of the cinema in relation to the other arts. There is no doubt that the cinema also could just as soon leave behind its classical period to enter a modern period. I think that in a few years, in ten, twenty or thirty years, we shall know whether Hiroshima was the most important film since the war, the first modern film of sound cinema, or whether it was possibly less important than we thought. In any case it is an extremely important film, but it could be that it will even gain stature with the years. It could be, too, that it will lose a little.

Godard: Like La Regle du feu on the one hand and films like Quai des brumes or Le Jour se !eve on the other. Both of Carne's films are very, very important, but nowadays they are a tiny bit less important than Renoir's film.

Rohmer: Yes. And on the grounds that I found some elements in Hiroshima less seductive than others, I reserve judgment. There was something in the first few frames that irritated me. Then the film very soon made me lose this feeling of irritation. But I can understand how one could like and admire Hiroshima and at the same time find it quite jarring in places.

Doniol-Valcroze: Morally or aesthetically?

Godard: Its the same thing. Tracking shots are a question of morality.'

Kass: It's indisputable that Hiroshima is a literary film. Now, the epithet 'literary' is the supreme insult in the everyday vocabulary of the cinema. What is so shattering about Hiroshima is its negation of this connotation of the word. It's as if Resnais had assumed that the greatest cinematic ambition had to coincide with the greatest literary ambition. By substituting pretension for ambition you can beautifully sum up the reviews that have appeared in several newspapers since the film came out. Resnais's initiative was intended to displease all those men of letters —whether they're that by profession or aspiration — who have no love for anything in the cinema that fails to justify the unforrnulated contempt in which they already hold it. The total fusion of the film with its script is so obvious that its enemies instantly understood that it was precisely at this point that the attack had to be made: granted, the film is beautiful, but the text is so literary, so uncinematic, etc., etc. In reality I can't see at all how one can even conceive of separating the two.

Godard: Sacha Guitry would be very pleased with all that.

Donioi-Vaicroze: No one sees the connection,

Godard: But it's there. The text, the famous false problem of the text and the image. Fortunately we have finally reached the point where even the literary people, who used to be of one accord with the provincial exhibitors, are no longer of the opinion that the important thing is the image. And that is what Sacha Guitry proved a long time ago. I say 'proved' advisedly. Because Pagnol, for example, wasn't able to prove it, Since Truffaut isn't with us I am very happy to take his place by incidentally making the point that Hiroshima is an indictment of all those who did not go and see the Sacra Guitry retrospective at the Cinematheque. 2

Doniol-Valcroze: If that's what Rohmer meant by the irritating side of the film, I acknowledge that Guitry's films have an irritating side. […] Essentially, more than the feeling of watching a really adult woman in a film for the first time, I think that the strength of the Emmanuelle Riva character is that she is a woman who isn't aiming at an adult's psychology, just as in Les 400 Coups little Jean-Pierre Laud wasn't aiming at a child's psychology, a style of behaviour prefabricated by professional scriptwriters, Emmanuelle Riva is a modern adult woman because she is not an adult woman, Quite the contrary, she is very childish, motivated solely by her impulses and not by her ideas. Antonioni was the first to show us this kind of woman.

Romer: Have there already been adult women in the cinema? Domarchi: Madame Bovary.

Godard: Renoir's or Minnelli's?

Domarchi: It goes without saying. (Laughter.) Let's say Elena, then.

Rivette: Elena is an adult woman in the sense that the female character played by Ingrid Bergman3 is not a classic character, but of a classic modernism, like Renoir's or Rossellini's. Elena is a woman to whom sensitivity matters, instinct and all the deep mechanisms matter, but they are contradicted by reason, the intellect. And that derives from classic psychology in terms of the interplay of the mind and the senses. While the Emmanuelle Riva character is that of a woman who is not irrational, but is not-rational. She doesn't understand herself. She doesn't analyse herself. Anyway, it is a bit like what Rossellini tried to do in Stromboli. But in Stromboli the Bergman character was clearly delineated, an exact curve. She was a 'moral' character. Instead of which the Emmanuelle Riva character remains voluntarily blurred and ambiguous. Moreover, that is the theme of Hiroshima: a woman who no longer knows where she stands, who no longer knows who she is, who tries desperately to redefine herself in relation to Hiroshima, in relation to this Japanese man, and in relation to the memories of Revers that come back to her. In the end she is a woman who is starting all over again, going right back to the beginning, trying to define herself in existential terms before the world and before her past, as if she were one more unformed matter in the process of being born.

Godard: So you could say that Hiroshima is Simone de Beauvoir that works. Domarchi: Yes. Resnais is illustrating an existentialist conception of psychology.

Doniol-Valcroze: As in Journey into Autumn or So Close to Life,4 but elaborated and done more systematically.

[…]

Domarchi: In fact, in a sense Hiroshima is a documentary on Emmanuelle Riva. I would be interested to know what she thinks of the film.

Rivette: Her acting takes the same direction as the film, It is a tremendous effort of composition. I think that we are again locating the schema I was trying to draw out just now: an endeavour to fit the pieces together again; within the consciousness of the heroine, an effort on her part to regroup the various elements of her persona and her consciousness in order to build a whole out of these fragments, or at least what have become interior fragments through the shock of that meeting at Hiroshima. One would be right in thinking that the film has a double beginning after the bomb; on the one hand, on the plastic level and the intellectual level, since the film's first image is the abstract image of the couple on whom the shower of ashes falls, and the entire beginning is simply a meditation on Hiroshima after the explosion of the bomb. But you can say too that, on another level, the film begins after the explosion for Emmanuelle Riva, since it begins after the shock which has resulted in her disintegration, dispersed her social and psychological personality, and which means that it is only later that we guess, through what is implied, that she is married, has children in France, and is an actress —in short, that she has a structured life. At Hiroshima she experiences a shock, she is hit by a 'bomb' which explodes her consciousness, and for her from that moment it becomes a question of finding herself again, re-composing herself. In the same way that Hiroshima had to be rebuilt after atomic destruction, Emmanuelle Riva in Hiroshima is going to try to reconstruct her reality. She can only achieve this through using the synthesis of the present and the past, what she herself has discovered at Hiroshima and what she has experienced in the past at levers.

Doniol-Valcroze: What is the meaning of the line that keeps being repeated by the Japanese man at the beginning of the film: 'No, you saw nothing at Hiroshima'?

Godard: It has to be taken in the simplest sense. She saw nothing because she wasn't there. for was he. However, he also tells her that she has seen nothing of Paris, yet she is a Parisian. The point of departure is the moment of awareness, or at the very least the desire to become aware, I think Resnais has filmed the novel that the young French novelists are all trying to write, people like Butor, Robbe-Grillet, Bastide and of course Marguerite Duras. I can remember a radio programme where Regis Bastide was talking about Wild Strawberries and he suddenly realized that the cinema had managed to express what he thought belonged exclusively in the domain of literature, and that the problems which he, as a novelist, was setting himself had already been solved by the cinema without its even needing to pose them for itself. I think it's a very significant point.

Kast: We've already seen a lot of films that parallel the novel's rules of construction. Hiroshima goes further. We are at the very core of a reflection on the narrative form itself. The passage from the present to the past, the persistence of the past in the present, are here no longer determined by the subject, the plot, but by pure lyrical movements. In reality, Hiroshima evokes the essential conflict between the plot and the novel. Nowadays there is a gradual tendency for the novel to get rid of the psychological plot. Alain Resnais's film is completely bound up with this modification of the structures of the novel. The reason for this is simple. There is no action, only a kind of double endeavour to understand what a love story can mean. First at the level of individuals, in a kind of long struggle between love and its own erosion through the passage of time. As if love, at the very instant it happens, were already threatened with being forgotten and destroyed. Then, also, at the level of the connections between an individual experience and an objective historical and social situation. The love of these anonymous characters is not located on the desert island usually reserved for games of passion. It takes place in a specific context, which only accentuates and underlines the horror of contemporary society. 'Enmeshing a love story in a context which takes into account knowledge of the unhappiness of others,' Resnais says somewhere. His film is not made up of a documentary on Hiroshima stuck on to a plot, as has been said by those who don't take the time to look at things properly. For Titus and Berenice in the ruins of Hiroshima are inescapably no longer Titus and Berenice.

Rohmer: To sum up, it is no longer a reproach to say that this film is literary, since it happens that Hiroshima moves not in the wake of literature but well in advance of it.5 "There are certainly specific influences: Proust, Joyce, the Americans, but they are assimilated as they would be by a young novelist writing his first novel, a first novel that would be an event, a date to be accorded significance, because it would mark a step forward.

Godard: The profoundly literary aspect perhaps also explains the fact that people who are usually irritated by the cinema within the cinema, while the theatre within the theatre or the novel within the novel don't affect them in the same way, are not irritated by the fact that in Hiroshima Emmanuelle Riva plays the part of a film actress who is in fact involved in making a film.

Doniol-Valcroze: I think it is a device of the script, and on Resnais's part there are deliberate devices in the handling of the subject. In my opinion Resnais was very much afraid that his film might be seen as nothing more than a propaganda film. He didn't want it to be potentially useful for any specific political ends. This may be marginally the reason why he neutralized a possible 'fighter for peace' element through the girl having her head shaved after the Liberation. In any case he thereby gave a political message its deep meaning instead of its superficial meaning.

Domarchi: It is for this same reason that the girl is a film actress. It allows Resnais to raise the question of the anti-atomic struggle at a secondary level, and, for example, instead of showing a real march with people carrying placards, he shows a filmed reconstruction of a march during which, at regular intervals, an image comes up to remind the viewers that it is a film they are watching.

Rivette: It is the same intellectual strategy as Pierre Klossowski used in his first novel, La Vocation suspenclue. He presented his story as the review of a book that had been published earlier, Both are a double movement of consciousness, and so we come back again to that key word, which is at the same time a vogue word: dialectic — a movement which consists in presenting the thing and at the same time an act of distancing in relation to that thing, in order to be critical — in other words, denying it and affirming it. To return to the same example, the march, instead of being a creation of the director, becomes an objective fact that is filmed twice over by the director. For Klossowski and for Resnais the problem is to give the readers or the viewers the sensation that what they are going to read or to see is not an author's creation but an element of the real world. Objectivity, rather than authenticity, is the right word to characterize this intellectual strategy, since the film-maker and the novelist look from the same vantage-point as the eventual reader or viewer. […] since we are in the realm of aesthetics, as well as the reference to Faulkner I think it just as pertinent to mention a name that in my opinion has an indisputable connection with the narrative technique of Hiroshima: Stravinsky. The problems which Resnais sets himself in film are parallel to those that Stravinsky sets himself in music. For example, the definition of music given by Stravinsky — an alternating succession of exaltation and repose — seems to me to fit Alain Resnais's film perfectly. What does it mean? The search for an equilibrium superior to all the individual elements of creativity. Stravinsky systematically uses contrasts and simultaneously, at the very point where they are used, he brings into relief what it is that unites them. The principle of Stravinsky's music is the perpetual rupture of the rhythm. The great novelty of The Rite of Spring was its being the first musical work where the rhythm was systematically varied. Within the field of rhythm, not tone, it was already almost serial music, made up of rhythmical oppositions, structures and series. And I get the impression that this is what Resnais is aiming at when he cuts together four tracking shots, then suddenly a static shot, two static shots and back to a tracking shot. Within the juxtaposition of static and tracking shots he tries to find what unites them. In other words he is seeking simultaneously an effect of opposition and an effect of profound unity.

Godard: It's what Rohmer was saying before. It's Picasso, but it isn't Matisse.

Domarchi: Matisse — that's Rossellini. (Laughter.)

Rivette: I find it is even more Braque than Picasso, in the sense that Braque's entire sure is devoted to that particular reflection, while Picasso's is tremendously diverse. Orson Welles would be more like Picasso, while Alain Resnais is close to Braque to the degree that the work of art is primarily a reflection in a particular direction.

Godard: When I said Picasso I was thinking mainly of the colours.

Rivette: Yes, but Braque too. He is a painter who wants both to soften strident colours and make soft colours violent. Braque wants bright yellow to be soft and Manet grey to be sharp. Well now, we've mentioned quite a few 'names', so you can see just how cultured we are, Cahiers du Cinema is true to form, as always. (Laughter.)

Godard: There is one film that must have given Alain Resnais something to think about, and what's more, he edited it: La Pointe courte.

Rivette: Obviously. But I don't think it's being false to Agnès Varda to say that by virtue of the fact that Resnais edited La Pointe courte his editing itself contained a reflection on what Agnes Varga had intended. To a certain degree Agnèsvarda becomes a fragment of Alain Resnais, and Chrismarker too.

Doniol-Valcroze: Now's the time to bring up Alain Resnais's 'terrible tenderness' which makes him devour his own friends by turning them into moments in his personal creativity. Resnais is Saturn. And that's why we all feel quite weak when we are confronted with him.

Rohmer: We have no wish to be devoured. It's lucky that he stays on the Left Bank of the Seine and we keep to the Right Banks.

Godard: When Resnais shouts 'Action', his sound engineer replies 'Saturn' riga tourne', i.e. 'it's rolling]. (Laughter.) Another thing — I'm thinking of an article by Roland Barthes on Les Cousins where he more or less said that these days talent had taken refuge in the right. Is Hiroshima a left-wing film or a right-wing film?

Rivette: Let's say that there has always been an aesthetic left, the one Cocteau talked about and which, furthermore, according to Radiguet, had to be contradicted, so that in its turn that contradiction could be contradicted, and so on As far as I'm concerned, if Hiroshima is a left-wing film it doesn't bother me in the slightest.

Rohmer: From the aesthetic point of view modern art has always been positioned to the left. But just the same, there's nothing to stop one thinking that it's possible to be modern without necessarily being left-wing. In other words, it is possible, for example, to reject a particular conception of modern art and regard it as out of date, not in the same but, if you like, in the opposite sense to dialectics. With regard to the cinema one shouldn't consider its evolution solely in terms of chronology. For example, the history of the sound film is very unclear in comparison with the history of the silent film, That's why even if Resnais has made a film that's ten years ahead of its time, it's wrong to assume that in ten years' time there will be a Resnais period that will follow on from the present one.

Rivette: Obviously, since if Resnais is ahead of his time he does it by remaining true to October, in the same way that Picasso's Las Meninas is true to Velazquez.

Rohmer: Yes. Hiroshima is a film that plunges at the same time into the past, the present and the future. It has a very strong sense of the future, particularly the anguish of the future.

Rivette: It's right to talk about the science-fiction element in Resnais. But it's also wrong, because he is the only film-maker to convey the feeling that he has already reached a world which in other people's eyes is still futuristic. In other words he is the only one to know that we are already in the age where science-fiction has become reality. In short, Alain Resnais is the only one of us who truly lives in 1959. With him the word 'science-fiction' loses all its pejorative and childish associations because Resnais is able to see the modern world as it is. Like the science-fiction writers he is able to show us all that is frightening in it, but also all that is human. Unlike the Fritz Lang of Metropolis or the Jules Verne of Ong cents millions de la Begum, unlike the classic notion of science-fiction as expressed by a Bradbury or a Lovecraft or even a Van Vogt all reactionaries in the end - it is very obvious that Resnais possesses the great originality of not reacting inside science-fiction. Not only does he opt for this modern and futuristic world, not only does he accept it, but he analyses it deeply, with lucidity and with love. Since this is the world in which we live and love, then for Resnais it is this world that is good, just and true.

Domarchi: That brings us back to this idea of terrible tenderness that is at the centre of Resnais's reflection. Essentially it is explained by the fact that for him society is characterized by a kind of anonymity. The wretchedness of the world derives from the fact of being struck down without knowing who is the aggressor. In Nuit et brouillard the commentary points out that some guy born in Carpentras or Brest has no idea that he is going to end up in a concentration camp, that already his fate is sealed, What impresses Resnais is that the world presents itself like an anonymous and abstract force that strikes where it likes„ anywhere, and whose will cannot be determined in advance. It is out of this conflict between individuals and a totally anonymous universe that is born a tragic vision of the world. That is the first stage of Resnais's thought. Then there comes a second stage which consists in channelling this first movement. Resnais has gone back to the romantic theme of the conflict between the individual and society, so dear to Goethe and his imitators, as it was to the nineteenth-century English novelists, But in their works it was the conflict between a man and palpable social forms that was clearly defined, while in Resnais there is none of that, The conflict is represented in a completely abstract way; it is between an and the universe. One can then react in an extremely tender way towards this state of affairs. I mean that it is no longer necessary to be indignant, to protest or even to explain. It is enough to show things without any emphasis, very subtly. And subtlety has always characterized Alain Resnais.

Rivette: Resnais is sensitive to the current abstract nature of the world. The first movement of his films is to state this abstraction. The second is to overcome this abstraction by reducing it through itself, if I may put it that way; by juxtaposing with each abstraction another abstraction in order to rediscover a concrete reality through the very act of setting them in relation to one another.

Godard: That's the exact opposite of Rossellini's procedure - he was outraged because abstract art had become official art.9 So Resnais's tenderness is metaphysical, it isn't Christian. There is no notion of charity in his films.

Rivette: Obviously not. Resnais is an agnostic. If there is a God he believes in, it's worse than St Thomas Aquinas's. His attitude is this: perhaps God exists, perhaps there is an explanation for everything, but there's nothing that allows us to be sure of it.

Godard: Like Dostoevsky's Stavrogin, who, if he believes, doesn't believe that he believes, and if he doesn't believe, doesn't believe that he doesn't believe. Besides, at the end of the film does Emmanuelle Riva leave, or does she stay? One can ask the same question about her as about Agnes in Les Dames du Bois de Boulogne, when you ask yourself whether she lives or dies.

Rivette: That doesn't matter. It's fine if half the audience thinks that Emmanuelle Riva stays with the Japanese man and the other half thinks that she goes back to France.

Domarchi: Marguerite Duras and Resnais say that she leaves, and leaves for good.

Godard: believe them when they make another film that proves it to me.

Rivette: I don't think it really matters at all, for Hiroshima is a circular film. At the end of the last reel you can easily move back to the first, and so on. Hiroshima is a parenthesis in time. It is a film about reflection, on the past and on the present. Now, in reflection, the passage of time is effaced because it is a parenthesis within duration. And it is within this duration that Hiroshima is inserted. In this sense Resnais is dose to a writer like Borges, who has always tried to write stories in such a way that on reaching the last line the reader has to turn back and re-read the story right from the first line to understand what it is about — and so it goes on, relentlessly. With Resnais it is the same notion of the infinitesimal achieved by material means, mirrors face to face, series of labyrinths. It is an idea of the infinite but contained within a very short interval, since ultimately the 'time' of Hiroshima can just as well last twenty-four hours as one second.

"<>"暂时没有网友评论该影片"}1959年,时任《手册》主编埃里克·侯麦组织了一场就《广岛之恋》的讨论会,参加的包括:埃里克·侯麦、让-吕克·戈达尔、Jean Domarchi、 雅克·多尼奥-瓦克罗兹、皮埃尔·卡斯特、雅克·里维特。这个英文版发表于Jim Hillier编辑的《电影手册,1950年代》结集一书中,翻译为Liz Heron。

In Cahiers no. 71 some of our editorial board held the first round-table discussion on the then critical question of French cinema Today the release of Hiroshima mon amour is an event which seems important enough to warrant a new discussion.

Rohmer: I think everyone will agree with me if I start by saying that Hiroshima is a film about which you can say everything.

Godard: So let's start by saying that it's literature.

Rohmer: And a kind of literature that is a little dubious, in so far as it imitates the American school that was so fashionable in Paris after 1945.

Kast: The relationship between literature and cinema is neither good nor clear. I think all that one can say is that literary people have a kind of confused contempt for the cinema, and film people suffer from a confused feeling of inferiority. The uniqueness of Hiroshima is that the Marguerite Duras—Alain Resnais collaboration is an exception to the rule I have just stated.

Godard: Then we can say that the very first thing that strikes you about this film is that it is totally devoid of any cinematic references. You can describe Hiroshima as Faulkner plus Stravinsky, but you can't identify it as such and such a film-maker plus such and such another.

Rivette: Maybe Resnais's film doesn't have any specific cinematic references, but I think you can find references that are oblique and more profound, because its a film that recalls Eisenstein, in the sense that you can see some of Eisensteinis ideas put into practice and, moreover, in a very new way.

Godard: When I said there were no cinematic references, I meant that seeing Hiroshima gave one the impression of watching a film that would have been quite inconceivable in terms of what one was already familiar with in the cinema. For instance, when you see India you know that you'll be surprised, but you are more or less anticipating that surprise. Similarly, I know that Le Testament du dotter Cordeher will surprise me, just as Eljna et les hornmes did. However, with Hiroshima I fee] as if I am seeing something that I didn't expect at all.

Rohmer: Suppose we talk a bit about Toute la memoire du monde. As far as I'm concerned it is a film that is still rather unclear. Hiroshima has made certain aspects of it clearer for me, but not all.

Rivette: It's without doubt the most mysterious of all Resnais's short films. Through its subject, which is both very modern and very disturbing, it echoes what Renoir said in his interviews with us, that the most crucial thing that's happening to our civilization is that it is in the process of becoming a civilization of specialists. Each one of us is more and more locked into his own little domain, and incapable of leaving it. There is no one nowadays who has the capacity to decipher both an ancient inscription and a modern scientific formula. Culture and the common treasure of mankind have become the prey of the specialists. I think that was what Resnais had in mind when he made Toute la memoir e du monde. He wanted to show that the only task necessary for mankind in the search for that unity of culture was, through the work of every individual, to try to reassemble the scattered fragments of the universal culture that is being lost. And I think that is why Toute la memoir du monde ended with those higher and higher shots of the central hall, where you can see each reader, each researcher in his place, bent over his manuscript, yet all of them side by side, all in the process of trying to assemble the scattered pieces of the mosaic, to find the lost secret of humanity; a secret that is perhaps called happiness.

Domarchi: When all is said and done, it is a theme not so far from the theme of Hiroshima. You've been saying that on the level of form Resnais comes close to Eisenstein, but it's just as much on the level of content too, since both attempt to unify opposites, or in other words their art is dialectical.

Rivette: Resnais's great obsession, if I may use that word, is the sense of the splitting of primary unity - the world is broken up, fragmented into a series of tiny pieces, and it has to be put back together again like a jigsaw. I think that for Resnais this reconstitution of the pieces operates on two levels. First on the level of content, of dramatization. Then, I think even more importantly, on the level of the idea of cinema itself. I have the impression that for Alain Resnais the cinema consists in attempting to create a whole with fragments that are a priori dissimilar. For example, in one of Resnais's films two concrete phenomena which have no logical or dramatic connection are linked solely because they are both filmed in tracking shots at the same speed.

Godard: You can see all that is Eisensteinian about Hiroshima because it is in fact the very idea of montage, its definition even.

Rivette: Yes. Montage, for Eisenstein as for Resnais, consists in rediscovering unity from a basis of fragmentation, but without concealingthe fragmentation in doing so; on the contrary, emphasizing it by emphasizing the autonomy of the shot.

It's a double movement - emphasizing the autonomy of the shot and simultaneously seeking within that shot a strength that will enable it to enter into a relationship with another or several other shots, and in this way eventually form a unity. But don't forget, this unity is no longer that of classic continuity. It is a unity of contrasts, a dialectical unity as Hegel and Domarchi would say. (Laughter.)

Doniol-Valcroze: A reduction of the disparate.

Rohmer: To sum up. Alain Resnais is a cubist. I mean that he is the first modern film-maker of the sound film. There were many modern filmmakers in silent films: Fisenstein, the Expressionists, and Dreyer too. But I think that sound films have perhaps been more classical than silents. There has not yet been any profoundly modern cinema that attempts to do what cubism did in painting and the American novel in literature, in other words a kind of reconstitution of reality out of a kind of splintering which could have seemed quite arbitrary to the uninitiated. And on this basis one could explain Resnais's interest in Guernica, which is one of Picasso's cubist paintings for all that it isn't true cubism but more like a return to cubism - and also the fact that Faulkner or Dos Passos may have been the inspiration, even if it was by way of Marguerite Duras.

Kast: From what we can see, Resnais didn't ask Marguerite Duras for a piece of second-rate literary work meant to be 'turned into a film', and conversely she didn't suppose for a second that what she had to say, to write, might be beyond the scope of the cinema. You have to go very far back in the history of the cinema, to the era of great naïveté and great ambitions - relatively rarely put into practice - to someone like a Delluc, in order to find such a will to make no distinction between the literary purpose and the process of cinematic creation.

Rohmer: From that point of view the objection that I made to begin with would vanish - one could have reproached some film-makers with taking the American novel as their inspiration - on the grounds of its superficiality. But since here it's more a question of a profound equivalence, perhaps Hiroshima really is a totally new film. That calls into question a thesis which I confess was mine until now and which I can just as soon abandon without any difficulty (laughter), and that is the classicism of the cinema in relation to the other arts. There is no doubt that the cinema also could just as soon leave behind its classical period to enter a modern period. I think that in a few years, in ten, twenty or thirty years, we shall know whether Hiroshima was the most important film since the war, the first modern film of sound cinema, or whether it was possibly less important than we thought. In any case it is an extremely important film, but it could be that it will even gain stature with the years. It could be, too, that it will lose a little.

Godard: Like La Regle du feu on the one hand and films like Quai des brumes or Le Jour se !eve on the other. Both of Carne's films are very, very important, but nowadays they are a tiny bit less important than Renoir's film.

Rohmer: Yes. And on the grounds that I found some elements in Hiroshima less seductive than others, I reserve judgment. There was something in the first few frames that irritated me. Then the film very soon made me lose this feeling of irritation. But I can understand how one could like and admire Hiroshima and at the same time find it quite jarring in places.

Doniol-Valcroze: Morally or aesthetically?

Godard: Its the same thing. Tracking shots are a question of morality.'

Kass: It's indisputable that Hiroshima is a literary film. Now, the epithet 'literary' is the supreme insult in the everyday vocabulary of the cinema. What is so shattering about Hiroshima is its negation of this connotation of the word. It's as if Resnais had assumed that the greatest cinematic ambition had to coincide with the greatest literary ambition. By substituting pretension for ambition you can beautifully sum up the reviews that have appeared in several newspapers since the film came out. Resnais's initiative was intended to displease all those men of letters —whether they're that by profession or aspiration — who have no love for anything in the cinema that fails to justify the unforrnulated contempt in which they already hold it. The total fusion of the film with its script is so obvious that its enemies instantly understood that it was precisely at this point that the attack had to be made: granted, the film is beautiful, but the text is so literary, so uncinematic, etc., etc. In reality I can't see at all how one can even conceive of separating the two.

Godard: Sacha Guitry would be very pleased with all that.

Donioi-Vaicroze: No one sees the connection,

Godard: But it's there. The text, the famous false problem of the text and the image. Fortunately we have finally reached the point where even the literary people, who used to be of one accord with the provincial exhibitors, are no longer of the opinion that the important thing is the image. And that is what Sacha Guitry proved a long time ago. I say 'proved' advisedly. Because Pagnol, for example, wasn't able to prove it, Since Truffaut isn't with us I am very happy to take his place by incidentally making the point that Hiroshima is an indictment of all those who did not go and see the Sacra Guitry retrospective at the Cinematheque. 2

Doniol-Valcroze: If that's what Rohmer meant by the irritating side of the film, I acknowledge that Guitry's films have an irritating side. […] Essentially, more than the feeling of watching a really adult woman in a film for the first time, I think that the strength of the Emmanuelle Riva character is that she is a woman who isn't aiming at an adult's psychology, just as in Les 400 Coups little Jean-Pierre Laud wasn't aiming at a child's psychology, a style of behaviour prefabricated by professional scriptwriters, Emmanuelle Riva is a modern adult woman because she is not an adult woman, Quite the contrary, she is very childish, motivated solely by her impulses and not by her ideas. Antonioni was the first to show us this kind of woman.

Romer: Have there already been adult women in the cinema? Domarchi: Madame Bovary.

Godard: Renoir's or Minnelli's?

Domarchi: It goes without saying. (Laughter.) Let's say Elena, then.

Rivette: Elena is an adult woman in the sense that the female character played by Ingrid Bergman3 is not a classic character, but of a classic modernism, like Renoir's or Rossellini's. Elena is a woman to whom sensitivity matters, instinct and all the deep mechanisms matter, but they are contradicted by reason, the intellect. And that derives from classic psychology in terms of the interplay of the mind and the senses. While the Emmanuelle Riva character is that of a woman who is not irrational, but is not-rational. She doesn't understand herself. She doesn't analyse herself. Anyway, it is a bit like what Rossellini tried to do in Stromboli. But in Stromboli the Bergman character was clearly delineated, an exact curve. She was a 'moral' character. Instead of which the Emmanuelle Riva character remains voluntarily blurred and ambiguous. Moreover, that is the theme of Hiroshima: a woman who no longer knows where she stands, who no longer knows who she is, who tries desperately to redefine herself in relation to Hiroshima, in relation to this Japanese man, and in relation to the memories of Revers that come back to her. In the end she is a woman who is starting all over again, going right back to the beginning, trying to define herself in existential terms before the world and before her past, as if she were one more unformed matter in the process of being born.

Godard: So you could say that Hiroshima is Simone de Beauvoir that works. Domarchi: Yes. Resnais is illustrating an existentialist conception of psychology.

Doniol-Valcroze: As in Journey into Autumn or So Close to Life,4 but elaborated and done more systematically.

[…]

Domarchi: In fact, in a sense Hiroshima is a documentary on Emmanuelle Riva. I would be interested to know what she thinks of the film.

Rivette: Her acting takes the same direction as the film, It is a tremendous effort of composition. I think that we are again locating the schema I was trying to draw out just now: an endeavour to fit the pieces together again; within the consciousness of the heroine, an effort on her part to regroup the various elements of her persona and her consciousness in order to build a whole out of these fragments, or at least what have become interior fragments through the shock of that meeting at Hiroshima. One would be right in thinking that the film has a double beginning after the bomb; on the one hand, on the plastic level and the intellectual level, since the film's first image is the abstract image of the couple on whom the shower of ashes falls, and the entire beginning is simply a meditation on Hiroshima after the explosion of the bomb. But you can say too that, on another level, the film begins after the explosion for Emmanuelle Riva, since it begins after the shock which has resulted in her disintegration, dispersed her social and psychological personality, and which means that it is only later that we guess, through what is implied, that she is married, has children in France, and is an actress —in short, that she has a structured life. At Hiroshima she experiences a shock, she is hit by a 'bomb' which explodes her consciousness, and for her from that moment it becomes a question of finding herself again, re-composing herself. In the same way that Hiroshima had to be rebuilt after atomic destruction, Emmanuelle Riva in Hiroshima is going to try to reconstruct her reality. She can only achieve this through using the synthesis of the present and the past, what she herself has discovered at Hiroshima and what she has experienced in the past at levers.

Doniol-Valcroze: What is the meaning of the line that keeps being repeated by the Japanese man at the beginning of the film: 'No, you saw nothing at Hiroshima'?